Why DiPS (Diagnose → Problem → Solution) thrashes meek tweaking

They set up A/B testing software, then change things like button colors or just shuffle items around the page because they read that it worked for someone else. They do the Garbage In → Garbage Out thing. In other words, if you put garbage into your A/B-testing software, you will get garbage out of it. (Albeit optimized garbage.)

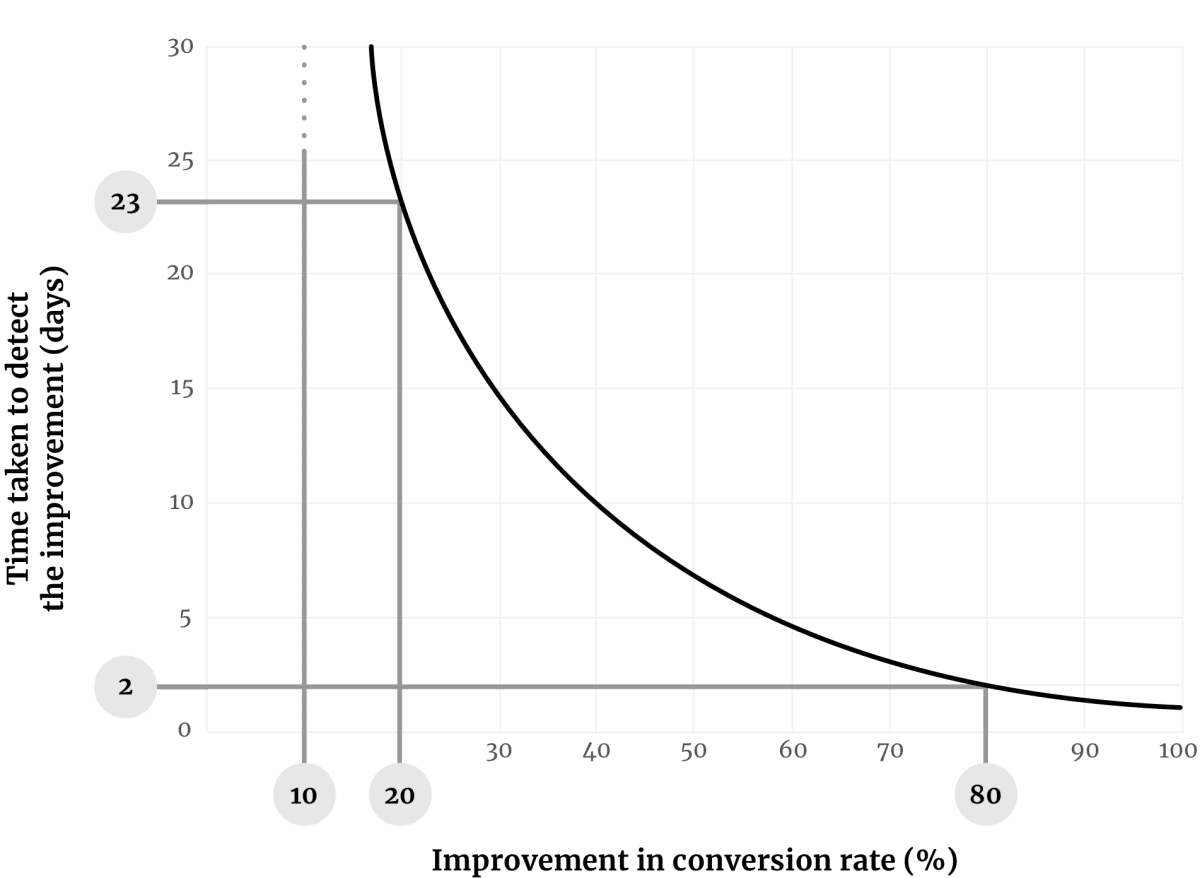

The following graph explains why meek tweaking is more harmful than it sounds.

In A/B tests, small improvements take much longer to detect.

The curved line shows how long it will take for an A/B test to reach completion based on the detected increase in conversion rate. It’s for a page that gets 300 views/day (that’s about 9,000 views/month). The shape of the curve would be similar (just higher or lower) for other traffic volumes.

Imagine that you have just designed a new version of such a page, and your new version has an 80% higher conversion rate than the existing version. As you can see in the graph, the time taken to detect that improvement would be just two days.

Whereas if your new version was only 20% better than the existing page, the A/B test would take twenty-three days to reach completion.

In other words, to detect an improvement that’s a quarter as large (20% compared with 80%), your A/B test would take over ten times as long (twenty-three days compared with two days).

If you were looking to detect an improvement of only 10%, then the A/B test would take several months to conclude.

The moral of the story is that small improvements take ages to detect, disproportionately and counterintuitively so.

Always aim for bold changes

You should aim for bold, targeted changes for the following reasons:

- Each change gets you more profit (an 80% improvement gives four times the benefit of a 20% improvement, obviously).

- It’s more fun and interesting.

- It’s much quicker.

Whereas if you’re doing what we call meek tweaking—making small, arbitrary changes, then your project suffers:

- You tend to get no wins. Your A/B tests never reach a conclusion.

- This becomes disheartening, and you lose motivation.

- You lose the buy-in from all the other people in your company whom you persuaded that A/B testing was going to be a good idea.

How to avoid meek tweaking (and ensure that your tests have a high likelihood of winning)

Most marketers do things to their websites that they’d never do to their bodies.

The most common causes of death in people are heart disease, cancer, stroke, respiratory infection, diabetes, and dementia.

However, on seeing that list, only a fool would rush to a pharmacy and start taking medication against all of those ailments, wolfing down pills for diseases they don’t have. Such behavior would cause more harm than good.

Instead, sensibly, when someone is ill, they go to a physician who first diagnoses what’s wrong and only then prescribes the most relevant remedy.

That may sound obvious for health, but it’s not what people do with their websites. Most web marketers run straight to the “marketing pharmacy” and cram their webpages with every possible remedy. Then they wonder why they have a website that’s cluttered and converts no better—or even worse—than the previous version. It’s marketing malpractice. Their visitors had specific objections, but instead of overcoming those objections, the marketers filled their pages with irrelevant distractions. They should be struck off.

Your visitors’ attention is limited. You must treat it preciously.

DiPS: A formula for success

The following approach to conversion is much more effective than the one described above. We call it Diagnose–Problem–Solution (DiPS for short). DiPS is the web-marketing equivalent of the physician doing tests to diagnose what is wrong, then analyzing the test data to identify the problem, and then coming up with an appropriate solution.

To implement DiPS, you first need to carry out research to diagnose your website’s problems. You’ll need to understand a lot about your visitors and how they interact with your website.

Conversion solutions are highly targeted; the problems are like locks—the solutions like keys

Here’s an example to illustrate why DiPS is so effective. And why the alternative—blindly applying best practices—is so ineffective.

Imagine that a company, InflataFish, had just launched a new product, the InflataRaft.

Would you buy one? Probably not, for one of the following reasons:

- You don’t know what it does.

- You know what it does, but you don’t know why you’d need one.

- You aren’t convinced that it will do what it claims to do.

- You don’t know whether it’s compatible with your existing technology.

- You think it’s too expensive.

- You don’t trust the company. You’ve never heard of them before.

- You are going to think about it.

If you don’t know what the InflataRaft does, InflataFish would have to explain what it does. Would a guarantee help instead? No. Would a lower price help instead? Not at all. Would testimonials help? No. None of those things would help one iota. The only thing that could advance your decision is an explanation of what the InflataRaft does—such as “InflataRaft is a durable, portable inflatable raft designed for easy setup and a variety of water-based activities.”

In fact, all those other solutions would merely reduce the chance that you’d ever find the paragraph that explains what the product does. The problem is like a lock, and the solution is like a key.

Now, imagine that you understand what the InflataRaft does, but can’t understand why that would benefit you. Would a guarantee help? No! Would a lower price help? No! Would a price discount help? No! The only thing that would advance your decision is an explanation of how the features relate to benefits that you care about—such as an explanation that “The InflataRaft is compact enough to fit into even the smallest dinghy, and auto-inflates in under 20 seconds.” That would do the job. Nothing else would.

And so for each objection, you need to display a clear counterobjection.

- If visitors don’t know what it does, then explain what it does.

- If visitors know what it does, but they don’t know why they’d need one, then explain the benefits.

- If visitors aren’t convinced that it will do what it claims to do, then add proof.

- If visitors don’t know whether it’s compatible with your existing technology, then explain the compatibility details.

- If visitors think it’s too expensive, then justify the price.

- If visitors don’t trust the company, then show evidence that the company is trustworthy.

- If visitors are going to think about it, then provide reasons to act promptly.

It’s the same with every single page element on a website. Every image and every word has a very specific purpose—usually to create a thought in the visitors’ minds that will move them closer to taking action.

Guarantees, for example, are mechanisms that have two very specific functions: to reduce risk and to demonstrate that the company is confident in its claims. So guarantees work only when risk and proof are issues. In other situations, they make no difference.

Negative headlines are another example of a mechanism. Negative headlines (such as “7 Mistakes to Avoid When Choosing a CRM”) work when the visitors have decided that they’ll do something (in this case, choose a CRM), and their main thought is “How can I avoid making the wrong decision?” In such cases, negative headlines work great; otherwise, they don’t.

Which type of marketer will you be?

Most marketers know some conversion mechanisms, but few understand each mechanism’s function. So they litter pages with “best practices”—a practice that’s far from best.

The best marketers don’t guess. They find out exactly why their visitors aren’t converting, then create funnels that counter each objection at the exact moment that the visitors think about it.

That’s why our methodology is grounded in research, and our client results are second to none.

How much did you like this article?

What’s your goal today?

1. Hire us to grow your company

We’ve generated hundreds of millions for our clients, using our unique CRE Methodology™. To discover how we can help grow your business:

- Read our case studies, client success stories, and video testimonials.

- Learn about us, and our unique values, beliefs and quirks.

- Visit our “Services” page to see the process by which we assess whether we’re a good fit for each other.

- Schedule your FREE website strategy session with one of our renowned experts.

Schedule your FREE strategy session

2. Learn how to do conversion

Download a free copy of our Amazon #1 best-selling book, Making Websites Win, recommended by Google, Facebook, Microsoft, Moz, Econsultancy, and many more industry leaders. You’ll also be subscribed to our email newsletter and notified whenever we publish new articles or have something interesting to share.

Browse hundreds of articles, containing an amazing number of useful tools and techniques. Many readers tell us they have doubled their sales by following the advice in these articles.

Download a free copy of our best-selling book

3. Join our team

If you want to join our team—or discover why our team members love working with us—then see our “Careers” page.

4. Contact us

We help businesses worldwide, so get in touch!

© 2026 Conversion Rate Experts Limited. All rights reserved.